Pure electric

by Christine Szustaczek – Apr 17, 2015

by Christine Szustaczek – Apr 17, 2015 Cars, technology and the chance to experiment and get involved — for Tony Orlando, part time Professor of Electrical Engineering at Sheridan, it’s a magical formula for inspiring successive cohorts of students to learn.

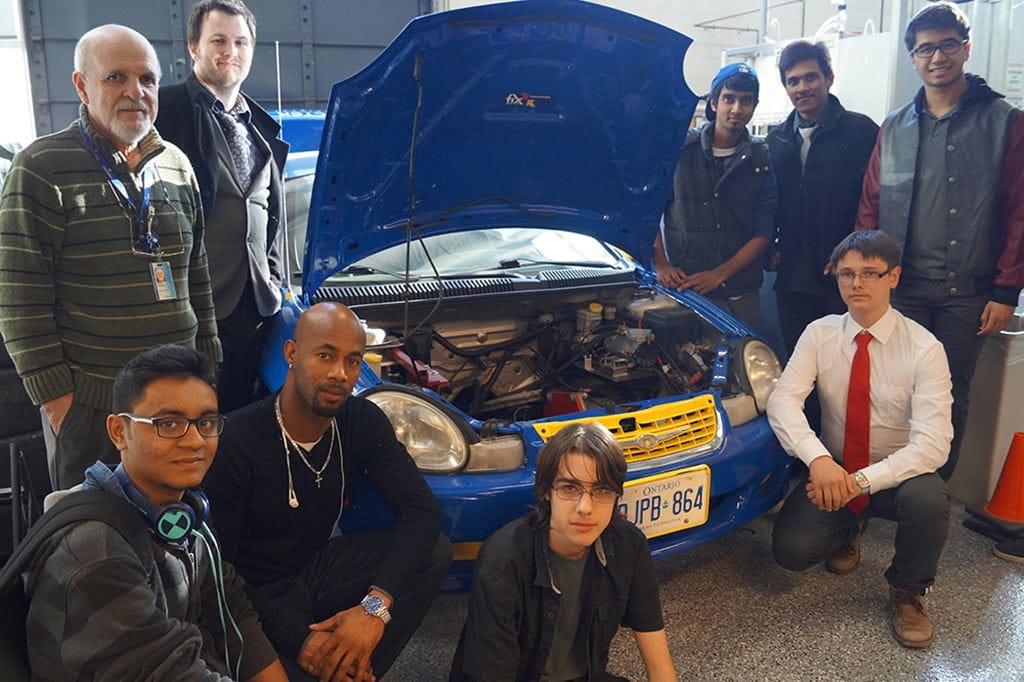

Orlando is the founder and supervising faculty member of Sheridan’s electric car project, an initiative of the Sheridan Engineering Club. It all began in 2009 when Mark Woods, a fundraiser who worked at Sheridan at the time, secured funds as well a donation of a 2002 Dodge Neon. The students were challenged to convert the Neon to a fully electric vehicle. It would take two years of project planning, and researching, prior to securing the required components before the actual work began.

“All of the work is done outside of the classroom by club members. What’s more – the students who designed the electric system never got to build it.” – Tony Orlando

“All of the work is done outside of the classroom by club members,” explains Orlando. “What’s more – the students who designed the electric system never got to build it,” he says, in reflecting on the length of electronics engineering diplomas at Sheridan. After the initial group graduated, that subsequent task fell to the second generation of club members.

“Over the span of four months, this next group of students removed all remnants of a gasoline powered car and replaced them with a state-of-the-art electronic system. The car was equipped with a three-phase AC electric motor, Curtis controller, state-of-the-art battery charger and a bank of eight lead acid batteries to supply the required current to the entire system. Small electric motors replaced belt driven pumps to supply power to the power steering and power brakes systems. Motor mounts, a battery container, and various other brackets had to be designed and built by the students to accommodate these changes.

As a safety feature, they installed an emergency shut off switch that disengages the system, as well as gauges mounted inside the car to monitor voltage levels and current usage. The batteries take about eight hours to charge, giving the car a top speed of about 80 km/hour and a total distance of about 30 kilometers before needing to be plugged in again. To emphasize the car’s purely electric design, the AC power inlet was purposely placed behind the fuel fill door where the car’s fuel intake was once located.

The car has toured a number of venues, the most exciting of which was a visit to the Chrysler assembly plant in Brampton during earth week 2013, where it was showcased on the production floor. Club members were on hand to answer questions, including Chris Peynado, who now serves as Club President. “In between shift changes, we were swarmed with people who wanted to see what we had done,” he said.

Orlando and Peynado are thrilled that work on the car continues with the help of an eager team of new club members – generation three. They’re working on replacing the original batteries which no longer hold their charge, and the tires, which are worn to the point that they’re affecting performance and safety. The car will also get a fresh coat of paint to reflect Sheridan’s new colours.

“To accommodate the electric system, 1,000 pounds was removed from under the hood, which changed the car’s centre of gravity. The batteries we put in the trunk weigh more than what was added under the hood. As a result, the car rides higher in the front than it should.” The new team will make changes to the suspension as well as replacing the heavy batteries with lighter ones to manipulate the height of the car and correct the centre of gravity issue.

“Because the car is purely electric, it’s so silent that people don’t hear us coming.” – Tony Orlando

In order to direct as much power into the engine as possible, the students who built the original system removed the car’s heaters and disconnected the wipers’ motor and the horn. According to Orlando, fixing the horn is a priority. “Because the car is purely electric, it’s so silent that people don’t hear us coming.”

The new team would also love to build and install a data acquisition system with sensors that detect energy consumption and a display to show various metrics in real-time. The students excitedly talk about running tests under different passenger loads and driving at different speeds to benchmark efficiency.

In Orlando’s mind, the project is a success because it ignites interest and supports students’ drive to learn. In short – it creates a feeling that’s pure electric.

Pictured at top of page: Members of Sheridan’s Engineering Club gathered around the electric car

Written by: Christine Szustaczek, Vice President, External Relations at Sheridan.

Media Contact

For media inquiries, contact Sheridan’s Communications and Public Relations team.