Pioneers of pedagogy and practice: The origin and evolution of Canada’s first Athletic Therapy program

by Christine Szustaczek – Jan 16, 2020

by Christine Szustaczek – Jan 16, 2020 The year was 1972. Ontario’s college sector was in its infancy, with member institutions like Sheridan having just turned five. Alongside dedicated schools for Heavy Equipment, Nursing, and Crafts and Design, Sheridan’s Brampton and Oakville campuses were home to budding programs in Visual Arts, Business and Secretarial, Early Childhood Education and English and Media Studies. Rounding out the student experience was a burgeoning program in varsity athletics, consisting of soccer, basketball, volleyball and hockey.

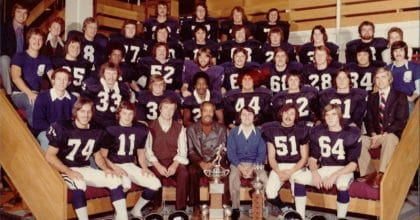

Looking to add varsity football to the mix, John Cruikshank, Sheridan’s early and enterprising Director of Athletics, hired Bernie Custis, former Grey Cup champion quarterback with the Hamilton Tiger Cats, to coach Sheridan’s nascent team. Cruikshank was adamant that the team deserved a professional athletic trainer, but quickly learned that no program existed in Canada to educate the kind of person he envisioned.

Undaunted, Cruikshank set off to create a program to fill the void, using a US-based university curriculum for inspiration. He pulled together an Advisory Committee that included physicians and surgeons, CFL and university trainers, physiotherapists, a university Dean of Physical and Occupational Therapy, and even a sports equipment manufacturer, who would likely know a thing or two about preventing injuries. Ministerial approval for Sheridan’s two-year diploma in Athletic Training and Management was secured, with a focus on preparing athletic trainers who could treat injuries and help manage a sports team.

Necessity as the mother of invention may explain the program’s impetus. Dig a little deeper and you’ll soon discover that it took root, and took shape, thanks to a successive team of pioneers who were united by a love of sport and human movement, a passion for helping others and a relentless determination to see their profession flourish.

For the love of sports

The program launched in September 1973, with Barry Bartlett, a former lecturer at the University of Toronto and professional lacrosse player, as the coordinator. With a Masters degree that focused on exercise physiology, Bartlett taught anatomy. Overseeing assessment and rehabilitation fell to Clyde Smith, a physiotherapist who Sheridan recruited from the University of Alberta. Rounding out the inaugural faculty were Cruikshank and Dick Ruschiensky, who taught biomechanics and did double duty as the coach of the men’s basketball team.

“If you looked at where trainers existed at the time, it was in pro-sport or at select colleges and universities,” explains Bartlett. “But every person practicing had a different background. No one was trained in Canada because there was nowhere here to study. There was only one sports medicine clinic in Canada, outside of the colleges and universities. There was no formal mechanism for physicians to be trained in sports medicine. That’s how green the field was.”

Bartlett estimates that fifty percent of the incoming class of about 20 students already had university degrees. Some were athletes. Others had volunteered to assist trainers on varsity teams. “They wanted to study academically. They wanted to learn things practically. And they wanted to help people.” In reflecting on what that composition meant for Sheridan’s program development, Bartlett says, “A conductor can only go as fast as the orchestra can play. Boy, did we have an orchestra that could play. For the first time in Canada, when people were watching a sports game on TV and wanted to become that person on the field, treating an injured player, we could say ‘we have a program for that’.”

One of the earliest students was Anne Hartley – who was among only five women admitted in the first cohort. Hartley had a physical and health education degree from the University of Toronto, an offer of admission to McMaster’s Medical School, and experience as an elite athlete, having won the Canadian Outdoor Archery Championship in 1972. It was her team doctor – a member of Cruikshank’s advisory panel – who suggested that she enter Sheridan’s new program while she was healing from back injuries and surgeries that prevented her from following her planned trajectory.

Hartley was hooked. Immediately upon graduation, she began working at Sheridan, partially teaching in the program and partially supporting the school’s teams. She was the first woman to hold the position of head athletic trainer at a Canadian college. “I know,” jokes Bartlett, “because we hired her.” The first woman to achieve the same feat at a Canadian university was another Sheridan alumna, Wendy Hampson, who was hired by Laurentian University in 1978.

Part of Hartley’s gig included supporting the men’s football team under the legendary Custis for about seven years. “Bernie was such a gentleman,” recalls Hartley. Custis ensured that the players listened to Hartley when she said they were sidelined due to injury. In return, Hartley promised that she’d never interfere with his coaching decisions. It was a relationship built on mutual respect and one that gave the role of a professional trainer immediate credibility.

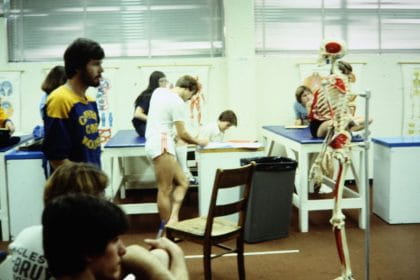

Hands-on from the start

Saying that the program had humble beginnings wouldn’t be a stretch. The school’s first clinic – primarily for treating Sheridan’s athletes – was in the basement. Even the early treatment tables required some ingenuity, with their bases constructed by a shop teacher at a nearby high school and the foam padding and covering donated by John Cooper, the program advisory committee member who owned the renowned Cooper Sports equipment company.

Despite the challenges, the milestones came quickly.

Seven months into the program, Peter Miller, who came to Sheridan with a baccalaureate degree and field trainer experience from Laurentian University, was offered a full-time job through his field placement with a junior hockey team. Miller never looked back – a decision that led to a career in which he earned five Stanley Cup rings with the Edmonton Oilers. “When Gretzky moved to LA, he convinced Peter to move with him,” adds Bartlett.

Next came the achievement of Joe Piccininni, who was also on a field placement with a junior hockey team. “A player had skated over a goaltender’s neck and slashed the artery that goes to the brain. Athletic therapists learn to react immediately on the field. Joe was able to jump into action and save the kid’s life,” explains Bartlett.

“For the first time in Canada, when people were watching a sports game on TV and wanted to become that person on the field, treating an injured player, we could say ‘we have a program for that’.” – Barry Bartlett

In year three, the 1976 Montreal Olympics provided a serendipitous opportunity for the program to gain widespread visibility. Smith and Piccininni volunteered on the core medical team supporting Canadian athletes, while Bartlett and Hartley took care of starts and finishes at races and assisted athletes from around the world. They, alongside Evert Van Beek (another faculty member) and countless Sheridan graduates to come would serve at numerous Olympic, Para Olympic, Commonwealth, Pan Am, Para Pan Am and Special Olympics Games to follow.

Gaining ground

Reflecting on the early days, Hartley says, “we faced a fair bit of rejection,” given that the field of Athletic Therapy wasn’t well recognized or understood. Bartlett recalls stories from students on field placements who tried to treat injuries using ice but were supervised by people whose formal training called for heat. “Even our association – which changed its name from Certified Athletic Trainers to Certified Athletic Therapists in 1976 – faced pushback from other associations who felt they owned the therapy name.”

The decision to include musculoskeletal assessment and rehabilitation as part of the program from the outset and hire people with a physiology background helped to establish credibility. Early professors in that domain included Van Beek who had a Masters degree with a focus in Exercise Physiology from Western University – a school known for their strong sports medicine physicians. Other professors such as Dan Devlin who replaced Clyde Smith, and later Judy Russell were both Athletic Therapists and Physiotherapists. Through such purposeful hiring, Sheridan ensured that the clinical components of its nascent program were taught to the same standard as in physiotherapy, which allowed the up and coming program to hold up to scrutiny.

Hartley’s role evolved to include running the program’s teaching and treatment clinic, which was growing in renown. Dr. Murray Duguid and Dr. Vern Isaak, who ran the college’s health centre, began sending student injuries to the clinic. Just as Hartley had won over Custis, she earned the trust of three orthopedic surgeons affiliated with the Oakville Hospital – Drs. Shepherd, Watkin and Davidson – after working summers in their fracture clinic. The trio began coming to Sheridan on Monday nights. With the clinic now open to the community, it meant that athletes from Sheridan – and from high schools and local sports teams – could be seen immediately. The program was growing in visibility. So too were parents’ understanding of and appreciation for the role.

Clinical work became a growing career path. A pioneer in that domain was Marcia Franklin. She deferred three university acceptances to get into Sheridan, “and I didn’t even get in on my first try,” she recalls, for lack of prior practical experience, which she spent a year accumulating before re-applying with success. After graduating and becoming professionally certified, Franklin would eventually run the program’s teaching clinic. In 1989, she opened the first private practice in Canada to strictly focus on Athletic Therapy, at a time when the discipline wasn’t a common treatment option for the average person. She began the practice as a sole clinician and eventually grew the business to employ 10 therapists who served thousands of patients. Joe Rotella, another Sheridan Athletic Therapy graduate, eventually worked with Franklin after completing a Masters degree at Indiana State University. He later became a professor, director and coordinator of the program.

Other alumni who ran successful practices included Rick Schaly who started Trainer’s Choice, Dave Wright who founded Mind to Muscle, and Rotella, who eventually left Sheridan to focus full time on his practice, Hamilton Osteopathic and Rehabilitation Centre, which had grown too large to manage while also teaching at Sheridan. Alumni began branching out into allied health and community services such as paramedicine and firefighting.

Hitting its stride

As a discipline that demands a growth mindset, faculty were among those who didn’t need any convincing to keep on learning. Hartley had gone back to school part time to become an Osteopathic Manual Practitioner, as did Rotella. Loriann Hynes, who entered Sheridan’s diploma program with an undergraduate university degree, earned both a Masters and a PhD specializing in head and neck biomechanics, with a research interest in whiplash and concussions. She too would serve as faculty and program coordinator, before moving to York University to oversee its program.

By 1987, the diploma program changed its name to Sports Injury Management, more accurately conveying its expanded focus on prevention, immediate care and rehabilitation. The field component included everything from taping, wrapping and bracing, to equipment and administering emergency care – whether it be a result of fractures, heat stroke or heart attacks. The clinical component covered anatomy, physiology, treatment modalities and rehabilitation.

Rotella remembers students being at placements every day and all weekend, logging enormous numbers of hours in addition to their studies. In 1990, the Sheridan diploma transitioned to a three-year program to create some breathing room and to allow for more elaborate courses, while retaining the practical component and practical exams needed to prepare graduates for professional life as an Athletic Therapist.

During the mid-90s, an articulation agreement was signed with the University of Guelph that ran for approximately eight years, in which students completed three years in their Human Kinetics program at Guelph before taking two years at Sheridan, allowing them to earn both a baccalaureate degree and diploma.

Constant partnership with the profession

As much as the program has been shaped by those at its heart, it has also been strongly influenced by its professional association – the Canadian Athletic Therapists Association (CATA).

“In the first 20 years of our program, there were numerous Sheridan faculty and graduates who went on to be President of the association” notes Bartlett. Others became Chair of Certification or Education. Many have served on a variety of committees. Several like Bartlett, Hartley, Franklin, Orecchio, Hynes and Rotella have been acknowledged as Hall of Famers or Distinguished Educators. Countless alumni have also served as executives in provincial chapters. “That tight connection has kept us cutting edge,” adds Elsa Orecchio, an alumna of the program who also served as a technologist, professor, clinic director, field placement supervisor and program coordinator before retiring in 2017. “We were right there when things were changing in the profession and often, we were leading the direction.”

As Athletic Therapy grew in popularity, so too did the number of people who sought to become a certified practitioner. Back in 1975, Hartley and Piccininni were among those who wrote the national certification exams in the first year they were offered and became certified Athletic Therapists. Recognizing the need for high quality and standardized preparation, CATA was encouraging post-secondary institutions to have their programs accredited.

“Nobody was really pursuing it,” recalls Rotella, “but we took it upon ourselves and spent a year putting together our application, showing every hour we devoted to anatomy, human physiology, placements, chemistry and more.” Sheridan’s application was unanimously accepted in 1998, making it the first accredited program in the country and a benchmark for others. “We were a college – somewhat over-shadowed at the time by universities. Our success pushed every other program in the country to formalize their programs,” says Rotella. Other accredited programs today include those at the Universities of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Concordia, York, Trois Rivieres, Mount Royal, and Camosun College.

“It’s not only injury we understand, it’s also the sport itself, and the athlete – their heart and soul and their mental capacity. We’re part of their team. We support them every day, at every stage. We also promote an active approach, which speeds up recovery.” – Elsa Orecchio

Turning point

When the Ontario Colleges of Applied Arts and Technology Act changed in 2002 to allow colleges to offer baccalaureate degrees, a window opened for the next phase of evolution.

“There was an explosion of information happening in healthcare and jobs in the field were increasingly demanding advanced degrees,” recalls Orecchio, an alumna of the program who also served as a technologist, professor, clinic director, field placement supervisor, and program coordinator before retiring in 2017. CATA was also specifying that individuals wishing to write the professional certification exams required a baccalaureate level degree.

Orecchio lead the process to move Sheridan’s advanced three-year diploma, to a four-year Bachelor of Applied Health Sciences (Athletic Therapy). Its mandate would be to provide students with advanced-level, discipline-specific skills, entrepreneurial and business skills to establish a successful professional practice, research skills to stay current with the latest developments and advance the body of professional knowledge, and a broader knowledge of culture and society to enhance their interactions with clients and patients.

Sheridan’s degree began in 2003. The extra year allowed for expanded material in manual therapy and new courses such as assessment and rehabilitation of the spine and an upper year course in emergency conditions. It is delivered in a competency-based learning framework and includes 1,200 practical hours – 600 on the field and 600 in the clinic.

“Athletic Therapists are capable of treating a wide range of patients, from children with concussions to seniors recovering from hip replacement surgery and everything in between.” – Paul Brisebois

Transitioning to a degree also required evidence that Sheridan’s courses were at the university standard. The University of Guelph and the University of Florida went on record to identify Sheridan’s degree as providing sufficient preparation for students wanting to pursue graduate studies. McMaster University and Queen’s University were other early advocates who accepted Sheridan’s degree graduates to Masters programs in Rehabilitation Sciences and Anatomy long before college degrees became more widely recognized and understood in Ontario.

Admittedly, this time of growth was not without some tension. Provincial regulations governing the creation of applied college degrees brought pressure to employ teaching faculty who had PhD degrees, even though up until that point, the discipline experts who taught in – and often founded – advanced college diploma programs in practical areas of study didn’t necessarily hold that terminal credential.

Dr. Trevor Cottrell became program coordinator. “He worked really well with the rest of the staff,” recalls Orecchio “and the staff very easily looked to him for leadership, because he was good at that.” In 2008, the program moved from its Oakville campus to a $23M, purpose-built facility at the Davis Campus in Brampton that provided both classroom and laboratory space for students as well as treatment space and new cutting-edge equipment for working with elite athletes and members of the public alike who experienced musculoskeletal injuries.

Maintaining program accreditation through CATA and Ministerial consent to offer the degree involve rigorous reviews that create ongoing opportunities for reflection. The first renewal in 2008 saw the creation of a mathematical formula that would replace the ‘hour-equals-a-credit’ model that was common in many college programs to accommodate the large number of practical hours in the degree while balancing the requirement for general education. During the 2015 review, a capstone course was added to give students a more enriched and independent thinking training process. “We wanted to prepare students for when they graduated,” said Hynes “by ensuring they’d know how to seek information on their own because we didn’t want them relying passively on just the things they learned as a student.”

Over the years, the professional advisory council has remained a mainstay, as have the partnerships with the Toronto Blue Jays, the Ottawa Redblacks, Canada Basketball, and countless other sports teams, clinics, schools, healthcare and community organizations, which provide placements for students to apply their knowledge and hone their skills. Alumni returning to work at Sheridan in a virtuous circle of knowledge sharing has also not changed. Paul Brisebois, an alumnus who was recognized with the Toronto Blue Jays Scholarship at the program’s convocation ceremony in 2003, is currently the program’s coordinator – a role he shared for a period of time with Kirsty McKenzie, who remains a professor in the program and Sheridan’s liaison with CATA.

The legacy and the future

Brisebois reports that over 1,500 students have graduated since the founding days, including Mike Burnstein and Chris Broadhurst, whose careers saw them serve as the head Athletic Therapists for the Vancouver Canucks and Toronto Maple Leafs respectively. More recent alumni have included Scott McCullough, head Athletic Therapist for the Toronto Raptors, Jon Sanderson, head Athletic Therapist with the Vancouver Canucks, Paul Papoutsakis, head Athletic Therapist for the National Ballet of Canada and Miranda Sallaway, head Athletic Therapist for the Cirque du Soleil show O at the Bellagio in Las Vegas.

From Hynes’ perspective, what distinguishes the profession is the fact that Athletic Therapists are “the only health care profession trained in the entire continuum of care, which includes injury prevention, recognizing and immediately managing injuries on the field, taking people through rehabilitation, and supporting them through to a return to activity.”

Orecchio adds, “It’s not only injury we understand, it’s also the sport itself, and the athlete – their heart and soul and their mental capacity. We’re part of their team. We support them every day, at every stage. We also promote an active approach, which speeds up recovery.”

Franklin puts it this way: “Unlike physiotherapy which has a wide scope of practice that treats stroke patients, burns, Cerebral Palsy and many other types of health and wellness, Athletic Therapy looks specifically at orthopedic injuries and conditions involving the muscles, bones and joints. We work with the physical body and try to correct what’s dysfunctional, not only to make it functional again, but to make it healthier.”

“Students are definitely realizing how to distribute their skills in different environments. I think we’re only just starting to see the potential of what the profession can do.” – Loriann Hynes

Franklin and Rotella point out that Athletic Therapists can help everyone. “Less than five percent of my clients are elite athletes,” says Rotella. “When I first graduated, people only saw an Athletic Therapist if their doctor told them to,” says Franklin. “Now people are taking their health into their own hands. As the population ages and continues to be more active, the notions of strength and conditioning are appealing to the masses.”

As Bartlett puts it, “This is not a program in Athletic Therapy. It’s a program in people . . . how you help them . . . how you prevent injuries . . . how you look after them when they’re hurt . . . and how you help them get back to however they define activity.”

“Although Certified Athletic Therapists are best known for their on-field and clinical care of amateur and professional athletes, it is the mix of on-site care and active rehabilitation skills that make graduates of the Sheridan Honours Bachelor of Applied Health Sciences-Athletic Therapy program specialists in assessing and treating all types of orthopaedic injuries,” explains Brisebois. “Utilizing a variety of manual therapies, modalities, exercise prescription, and bracing and taping, Athletic Therapists are capable of treating a wide range of patients, from children with concussions to seniors recovering from hip replacement surgery and everything in between. Using a unique and active approach to rehabilitation, Athletic Therapists empower each patient with the ability to return to their healthy and active lifestyle.”

In thinking back on her time with the program, what stands out most for Orecchio are the professors and the students. “The faculty are the best of the best in their disciplines. They’re so deeply reflective of their own skills and routinely look for new ways to share course materials or modify the curriculum to meet the changing needs of the profession. Most of all, they make it their mission to engage with students on a one-to-one basis. And we have the greatest students. That’s what I miss the most. Being in the classroom with them was sheer joy.”

Hynes sums it up this way. “Students are definitely realizing how to distribute their skills in different environments. I think we’re only just starting to see the potential of what the profession can do.”

Read about six Sheridan alumni whose work helps define the field of athletic therapy.

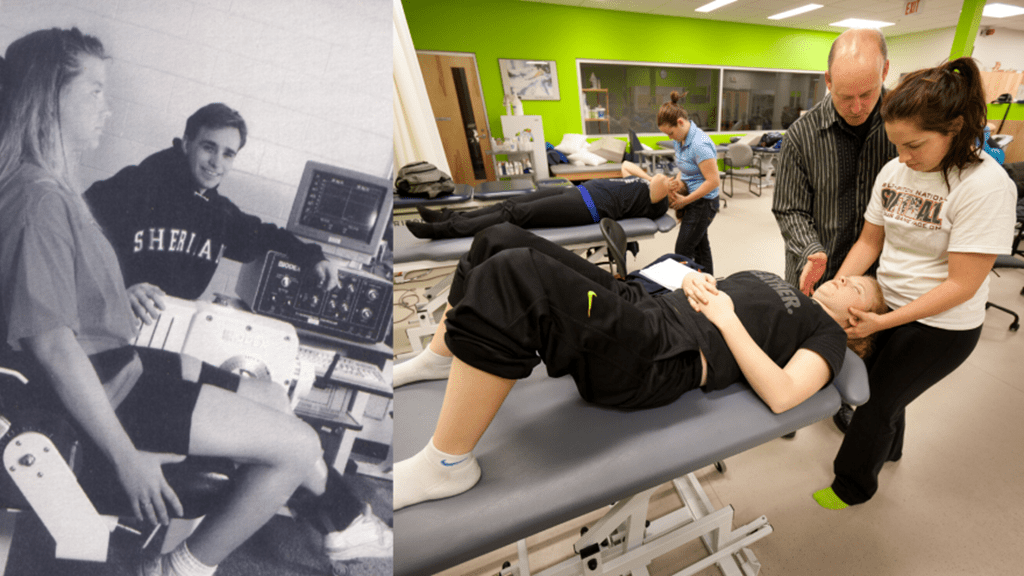

Pictured at top of page (left to right): Students in the Athletic Therapy program in the 1980s and students and a professor in the Athletic Therapy Clinic in 2014.

Written by: Christine Szustaczek, Vice President, External Relations at Sheridan.

Media Contact

For media inquiries, contact Sheridan’s Communications and Public Relations team.