Preserving Indigenous history and culture through story

by Jon Kuiperij – Feb 12, 2020

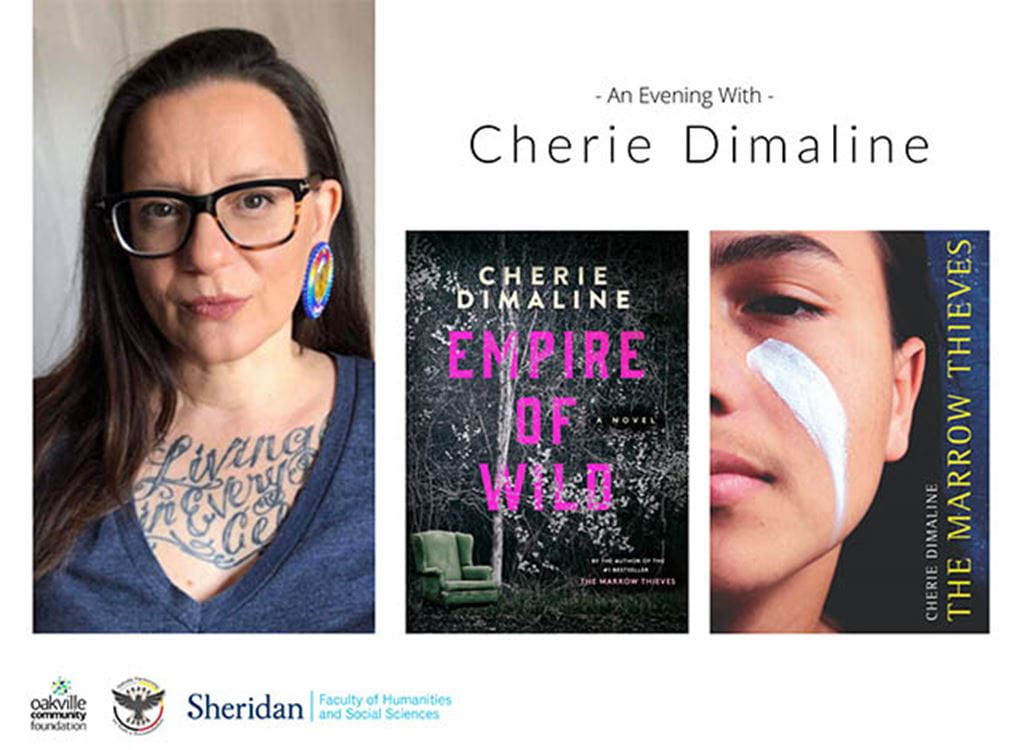

by Jon Kuiperij – Feb 12, 2020 Award-winning Métis writer Cherie Dimaline recently visited Trafalgar Campus to discuss her responsibilities as an Indigenous storyteller and explain how land and space influence her writing.

“Our land is disappearing, and so much of who we are has to do with that land,” Dimaline told the crowd that attended the event in The Marquee, Sheridan’s Student Union venue. “I’ve realized the only way my kids will have an understanding of what our land is, and therefore who they are and what their responsibilities are, is if I keep that place home through stories.”

The evening of conversation was the first installment of Sheridan’s Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences’ C² = The Creativity Calendar, an initiative which will bring notable speakers and activities related to creativity to the Sheridan community throughout the Winter 2020 term. Griffin Prize-winning poet Liz Howard, the inaugural writer-in-residence of Sheridan’s Honours Bachelor of Creative Writing and Publishing degree, interviewed Dimaline on stage for 45 minutes before the two fielded questions from the audience.

Land is a character

Howard led off the conversation by noting how Empire of Wild, Dimaline’s latest novel and Indigo’s #1 Best Book of 2019, was descriptively set in the Georgian Bay area where Dimaline grew up. “Land is absolutely present as a character in all of my writing,” responded Dimaline, whose mother is Métis with Anishinaabe and Menominee ancestry. “It’s not something I do on purpose, it’s just that one of the parents who raised me was the land.”

Much of that land has since been developed and is now unrecognizable, Dimaline noted. “Part of the impetus for the speed I’m writing at is that the land is everything. It’s where the stories come from and it’s who we are, and I’m watching it be pulled away. (Writing about it) is a way I can always ensure there’s space for all the kids,” she said. “It’s like inhaling really deep to feel the flex and curve of your lungs, just to know you can breathe. So when we can’t always be on the land, we are always on the land.”

Indigenous stories contain history or lessons

Discussion then shifted to Dimaline’s responsibilities as an Indigenous storyteller, responsibilities she has held since her youth. “My grandmother kept stories for the community, which was so important because we’d been relocated so many times. My role was to listen and then eventually, after a few years, my job was to tell those stories back,” Dimaline recalled.

There were two types of stories: those that contained the community history, describing traplines that went into the north, allies and enemies; and those that contained a lesson. The former had to be recited back exactly the same “because they were our textbooks and our maps”, while the latter had to be told “differently, but the same. They wanted me to know how to recognize what the teaching was that had to be passed along, and also for me to prove I could weave a basket of words to carry that teaching properly and be able to deliver it.”

“I’ve realized the only way my kids will have an understanding of what our land is, and therefore who they are and what their responsibilities are, is if I keep that place home through stories.”

One of those stories — the legend of the Rogarou, a mythical werewolf-like creature in Métis communities — later became the inspiration for Empire of Wild. After sharing that story as an impromptu 40-minute speech at an event where she thought she’d simply be part of a guest panel, Dimaline was approached by a fellow writer who asked if she’d written extensively about the Rogarou before. “That was the day I knew I needed to write about it,” Dimaline said. “Then I thought of someone trying to colonize the Rogarou, and then it became about resource extraction and the role the church plays in making us vulnerable to that extraction.”

Sharing stories can help settlers ‘understand how to be better’

Other topics of conversation included the television adaption of Dimaline’s Governor General Literary Award-winning novel The Marrow Thieves; an Indigenous renaissance in arts and literature; the delicate balancing act of writing for cultural preservation and for entertainment; and the challenges in deciding which stories to share with non-Indigenous audiences and which ones should remain untold.

Dimaline spoke of her recent interaction with Sto:lo poet Lee Maracle after Maracle told a story in a Hamilton coffeehouse that Dimaline had only heard before in ceremony. “I told her I wasn’t judging her, but I wondered why she told it at an event where I thought there was maybe one Indigenous person in the audience,” Dimaline said. “She said, ‘Because we’re at a time where the western way of doings things has brought us to the end. We want settlers to do better. We need them to do better. We ask them to do better, but we don’t give them the stories they need to understand how to be better on our land… From now on, I’m going to start telling these stories more often because I truly want them to do better for all of us.’”

An Evening With Cherie Dimaline was presented in partnership with the Oakville Community Foundation and in support of the Oakville Partnership on Truth and Reconciliation. The next C² = The Creativity Calendar event is scheduled for Feb. 13, when playwright and acclaimed CBC broadcaster Amanda Parris will visit Davis Campus for a conversation in celebration of Black History Month.

Pictured at top of page: Award-winning Métis writer Cherie Dimaline. Photo by Robin Sutherland.

Written by: Jon Kuiperij, Marketing Copy/Content Writer at Sheridan.

Media Contact

For media inquiries, contact Sheridan’s Communications and Public Relations team.