Sheridan’s first Indigenous graduate returns after 53 years to share his story and artistic talents

by Olivia McLeod – Jun 26, 2023

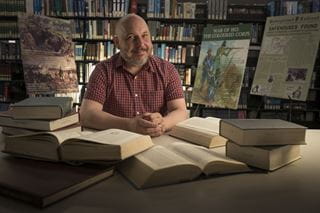

by Olivia McLeod – Jun 26, 2023  Being back on Sheridan’s Trafalgar Campus was a homecoming for Rene Meshake (Graphic Design, ’70). Fifty-three years after becoming the first Indigenous graduate, he is now an Anishinaabe Elder who has become a visual and performing artist, an award-winning author, storyteller, flute player, new media artist and a recipient of Queen Elizabeth II’s Diamond Jubilee Medal.

Being back on Sheridan’s Trafalgar Campus was a homecoming for Rene Meshake (Graphic Design, ’70). Fifty-three years after becoming the first Indigenous graduate, he is now an Anishinaabe Elder who has become a visual and performing artist, an award-winning author, storyteller, flute player, new media artist and a recipient of Queen Elizabeth II’s Diamond Jubilee Medal.

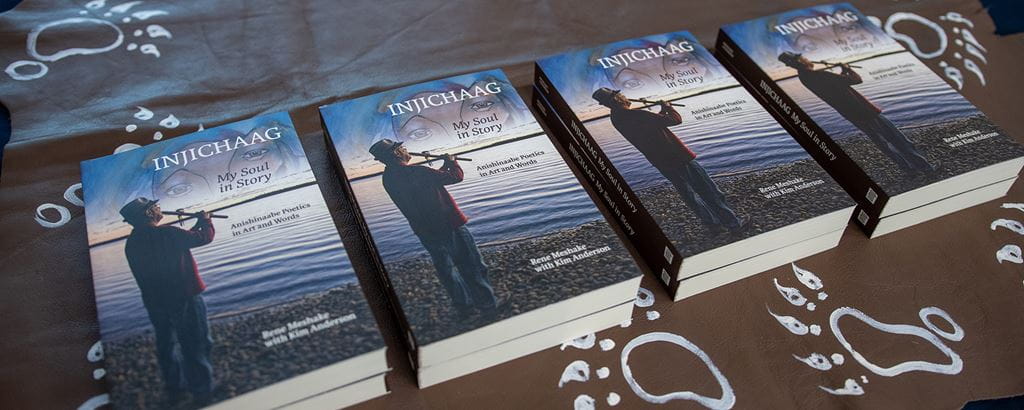

In celebration of National Indigenous History Month, Meshake, accompanied by his wife Joan (whom he affectionately refers to as his “boss”), ventured back to Sheridan to share his time and his story with the school community in a poignant and engaging conversation. Reading excerpts from his book Injichaag: My Soul in Story: Anishinaabe Poetics in Art and Words, as well as performing with his collection of pipigwan flutes, he says coming back to campus gave him a sense of validation he had been searching for.

At 75, Meshake is still creating beautiful artworks using a host of different mediums. His newest series will be 14 paintings focusing on his beloved instrument, titled Pipigwan Flute Tablatures. Funded through a grant from the Canada Council for the Arts, the paintings will be his continued attempt at what he calls “making the turtle dance”, the turtle being a reference to the term many Indigenous peoples recognize as the original name for North America, Turtle Island. “Making the turtle dance” is his way of sharing many years of wisdom through art in effort to inspire others to do the same.

Born in the railway town of Nakina in northwestern Ontario in 1948, Meshake spent his early years living off-reserve with his grandmother in a matriarchal land-based community he calls Pagwashiing. He recalls his grandmother’s life lessons in her “bush university,” where he learned to live off the land he was raised on.

Then, at age 10, he was forced into the residential school system. He suffered years of sexual and physical abuse, as well as the loss of language and connection to his family and community. The experience completely changed his young life, suffocating his artistic expression and resulting in decades of struggle, including substance abuse and homelessness.

“I lived in Toronto when I was homeless,” he says. “It was over six years of my life, and I was only able to make it out of there because of rehab. I completed my eight-month stay in 1991 and as of this year I will be 32 years sober.”

One constant in his life has always been art and artistic expression. In residential school he could only draw Christian art and was shamed for his Anishinaabe drawings. But when he left the residential school and went to high school in Thunder Bay, a guidance counsellor saw his potential and recommended Sheridan’s program. It was here, in 1969, that Meshake became part of the Bruin (or makwa – the word for bear in his Anishinaabe language) community, and started to embrace his cultural roots through art once again.

“We were all hippies” he recalls. “And the other students thought I was cool because we all stood for the same values. I felt comfortable around them. I could also grow my hair long again, which is very meaningful to my culture. I was forced to cut it all off in residential school and high school.”

It was at Sheridan where Meshake says he learned, “everything I know about graphic design.” The practices and techniques he studied while in school are tools he still utilizes today, like painting to music (Jimi Hendrix was a main inspiration) and working with different artistic mediums.

He has specifically embraced the latter in recent years, turning to new AI technologies to enhance his mixed media artworks, often under the name “The Funky Elder.” His son, an avid video game player, was the inspiration for this venture. Watching him play and seeing the different concept art used to create these games gave Meshake the idea to create concept art of his own, utilizing new technology to do so.

“I like combining songwriting, painting and AI to create these animated videos. I use my painting to create an AI background for my art and overlay that with my original music,” he says. “I call it video art.”

Meshake has always found solace in his art and music. Realizing that his gift was to share his music and art with the world and “make the turtle dance,” he now hopes his life’s work – in any medium – will serve as an inspiration to future generations. He hopes to specifically inspire Indigenous youth, saying, “everything I do, my book and my art, is dedicated to the younger generation. I want to inspire hope in them.”

Media Contact

For media inquiries, contact Sheridan’s Communications and Public Relations team.