Indigenous storytelling and giving back through game design

by Meagan Kashty – Jun 21, 2019

by Meagan Kashty – Jun 21, 2019 Meagan Byrne is all about the long game.

Whether it be her career as a game designer, the establishment of her game studio, or advocating for Canada’s Indigenous community, the Métis game designer isn’t one to cut and run from a challenge.

Byrne is the co-founder of Hamilton-based Achimostawinan Games and the first digital and interactive co-ordinator at imagineNATIVE — the world’s largest Indigenous film and media-arts festival. Her goal in both roles, she says, is to help tell Indigenous stories in more interactive and engaging ways.

“I want to tell stories from a modern perspective,” explains Byrne. “Indigenous stories that look towards the future, rather than just the past. I want to show that Indigenous games and other media can be entertaining, not just educational.”

Achimostawinan — which means “tell us a story” in Cree – was founded by Byrne and Tara Miller, a fellow Sheridan student, while Byrne studied Game Design at Sheridan. But it’s only in the past year or two that the pair have focused on growing the company, as Miller completes her Animation degree.

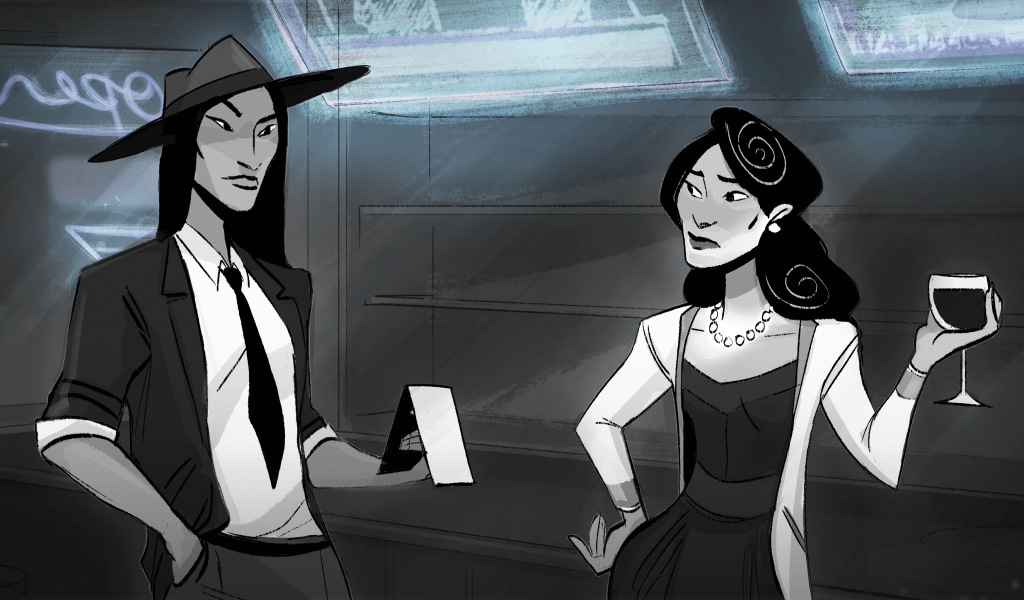

Their debut game, Purity and Decay (now called Hill Agency), epitomizes Achimostawinan Games’ mandate to tell stories for Indigenous audiences. Set in 2062, Hill Agency follows private eye Myeengun Hill as she attempts to solve a young woman’s murder. Characterized as “Indigenous cybernoir,” the game’s character names and locations are taken from Byrne’s and Miller’s specific nations, while the storyline is a subtle reference to the modern reality of Canada’s Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. A prototype of the game was released in 2017, and today, Byrne and the growing team of Indigenous game designers at Achimostawinan Games are developing it for a publisher.

At imagineNATIVE, Byrne will lead the first-ever iNdigital Space during the festival — a large-scale presentation of digital and interactive Indigenous works, including VR games, online platforms and digital web series. The festival will take place from Oct. 22 to 27.

Byrne’s work with both imagineNATIVE and Achimostawinan Games is about helping provide other Indigenous youth the same opportunities she was afforded. Storytelling is such an important part of her culture, says Byrne, that she feels a responsibility to help other Indigenous people share their stories in their own way.

“I was very lucky to grow up near Toronto, and have both my parents alive, working, and able to contribute to my education. I’ve had every opportunity afforded to me, but I still struggle to make it as a game designer,” she says. “For someone living on a remote reserve trying to do the same thing, they have even more barriers to overcome. I’m trying to figure out ways to work to give back to the next generation.”

Growing up in Hamilton, Byrne wasn’t told she was Métis until she was a pre-teen. She recalls going to her first Indigenous community event, where a friend of her aunt’s asked prodding questions about Byrne’s upbringing, concluding that she “wasn’t very Native.”

“This was before I was familiar with terms like intergenerational trauma, or lateral violence,” explains Byrne. “For a young kid who couldn’t understand the complexities of the situation and didn’t have a community or elder to turn to, it was really hard.”

Resources at Sheridan, says Byrne, enabled her to connect to her culture and navigate the complexities of her Métis heritage.

Sheridan’s Centre for Indigenous Learning and Support provided a lot of support to Byrne during her college years. She specifically remembers Paula Lang, Manager for Indigenous Affairs, always being open to guiding students to their next steps. Sheridan connected Byrne to other Métis communities and elders, giving her a support network to turn to.

Coming in as a more mature student – Byrne already had two degrees under her belt before she began Sheridan’s Game Design program — she says she was in a unique position embrace Sheridan’s program wholeheartedly.

“I wasn’t interested in just waiting to see if the program clicked – I wanted to take what was being taught and apply it straight away,” she says. “I wasn’t an avid gamer before I started the program, but I think that served me well. I didn’t have any preconceived notions of what makes a ‘good’ game, so I wasn’t rejecting anything offhand.”

“I want to tell stories from a modern perspective. Indigenous stories that look towards the future, rather than just the past. I want to show that Indigenous games and other media can be entertaining, not just educational.”

Eventually, Byrne decided to focus her energy on developing games featuring Indigenous stories. In 2015, during her second year at Sheridan, she developed her first solo game. Wanisinowin / Lost features a young girl from the spirit world, whose life is turned upside down when she learns she’s not actually a total spirit, but also a human. The character of Wani is loosely based on Byrne’s own experiences exploring her Indigenous background, and Sheridan’s Lang inspired the guide character.

While in school, Byrne connected with as many game designers and associations as possible. “It was all about planning, testing, and failing quickly, so I could apply any tips I picked up to my career,” she explains. “I knew that the first ten times I did anything; it was going to suck. But if I could learn from my mistakes, and find people to connect with in the game development community, that’s what was important.”

Today as a graduate, Byrne regularly shares her skills by running game design camps for Indigenous youth and volunteering for Canada Learning Code. She also sits on the board of directors for Dames Making Games — the same organization she connected with as a student. The non-profit encourages the participation of women, non-binary, femme and queer people in the creation of video games. Additionally, Byrne is also the co-director of Indigenous Routes, which helps to provide new media training to Indigenous Youth to help them develop their artistic skills in digital media, so they can share their work on a global scale.

“I’ve found so much value in giving back, even when I haven’t had much to give,” says Byrne. “Even if you aren’t coming from a place of trauma, there are so many ways to help. Even though I didn’t grow up in the Métis community, the more I gave, the more I’ve gotten back in terms of understanding what work I should be doing and where to focus my attention.”

Written by: Meagan Kashty, Digital Communications Officer at Sheridan.

Media Contact

For media inquiries, contact Sheridan’s Communications and Public Relations team.